Missives and Missiles

The Falklands War

War in the South Atlantic began over lunch. On Dec. 9, 1981, Argentinian General Leopoldo Galtieri met with Admiral Jorge Anaya to talk about when and how to overthrow President Roberto Viola. Anaya offered to support Galtieri if the navy was allowed to take the Falkland Islands and South Georgia away from the United Kingdom.

Viola was the country’s second president since 1976, when the Argentinian military took control away from Isabel Peron. The military dictatorship had been brutal, torturing and killing thousands of citizens in what became known as the “Dirty War”. By 1981, the country was economic crisis. That year the inflation rate hit 600%, the economy shrank 11% and real wages dropped by 19%. Despite repression, public opposition led by labor unions was escalating.

Galtieri agreed with Anaya and was soon installed as the new president. Like many leaders beset by domestic troubles, he thought a fight against an external enemy would provide a splendid distraction.

Great Britain had been disputing sovereignty of the Falkland Islands since they were settled in 1764, first with France, then with Spain and most recently with Argentina. Economically insignificant, they were treated as strategically important, as Graf von Spee found to his dismay when he tried to raid Port Stanley for coal and supplies in 1914.

More importantly, the two Argentinian military leaders thought that flying the their flag over the capital of Port Stanley on what Argentina calculated would be 150th anniversary of the “illegal usurpation of Las Malvinas” would lead to a new era of national pride and guarantee Galtieri a decade in power.

Because Argentina was helping the United States to support the Contra (anti-Communist) guerrillas in Nicaragua, Galtieri calculated that the Americans would stay clear of any conflict. Based on its behavior in Suez in 1956 and more recently in agreeing to let go of Rhodesia, he figured that Britain would not mount any serious obstacle to Anaya’s ambitions. A speedy victory in taking over the Falkland Islands would rally Argentinians around their flag and brush aside concerns about the economy and human rights.

On April 2, 1982, Argentine troops invaded the islands and occupied Port Stanley. While they succeeded in the Falkland Islands and South Georgia, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was not the type to back down.

The war proved more costly than either side expected. The Argentinian navy had its light cruiser General Belgrano sunk by British nuclear-powered submarine Conqueror on May 2. Two days later the British lost destroyer Sheffield to an aircraft-launched Exocet missile.

On May 21, the British successfully landed 4,000 men from the 3 Commando Brigade on East Falkland. Between May 21 and 25, however, they lost four more ships (and another two damaged) to Argentinian air attacks. The British continued to land troops, and on June 14, the last Argentinian troops on the island surrendered at Port Stanley. Over the 74-day conflict, 907 people died, 649 from Argentina and the rest from British forces and Falkland Island civilians.

Because of the size of this unexpected air-sea conflict with modern weapons, the Falklands War became the subject of much military analysis. It also became the subject of several games. Two were released before 1982 was out.

The first, published by Mayfair, was War in the Falklands. This is a fairly small game with only 150 counters, but it covers the actions of all the land, sea and air units involved. The map is divided into 14 areas, and the game is played for a maximum of 12 turns.

All the ships involved have individual named counters. Air units are identified by type. British units consist of Harrier jump jets, Vulcan long-range bombers and Sea King helicopters.

The main Argentinian air forces include Mirage and (Israeli-made) Knesher fighters, and Super Étendard and Skyhawk attack aircraft. However, the Argentinian counter mix also includes outdated Canberra medium bombers from the 1940s, retired F-86 Sabre fighters from the 1950s that were re-activated for air defense, Neptune surveillance and anti-submarine planes, and C-130 cargo planes that were used to ferry paratroopers.

There is even a counter for the squadron of Peruvian Mirage 5 fighters that was offered to Argentina late in the conflict but which never saw action.

The game starts with the Argentinians in control of both the Falklands and the island of South Georgia. Britain must move quickly to take the latter or suffer a huge victory point penalty as the game goes on. For the most part, victory points accumulate each turn from control of the islands and surrounding seas, and from the elimination of enemy units.

The game rules neatly meld the interactions between land, air and naval units. They are only seven pages long, but they cover the movement of ships, submarines and infantry at sea, that of aircraft and helicopters through the air as well as that of infantry on land. There are special rules for British assault ships and helicopter shuttles, Argentinian paratroops and the British Special Boat Service.

The rules cover air to air, air to sea, air to land, ship to ship and land to land combat, which are resolved each turn in that order.

Also highlighted in the game is the impact of missiles on modern combat. Within each type of combat except land to land, there is a missile round followed by a close combat round. The only units able to fire in the missile round are those equipped with long-range missiles (including the Tigerfish torpedoes carried by British submarines). Within each round, firing is simultaneous.

The game pieces show combat values in an unusual way. These values range from a low of 5 to a high of 12. In this game, however, lower values are better. To score a hit, a unit must roll equal to or higher than its combat value on two six-sided dice. Values that can be used in missile combat rounds are circled. Land units and larger ships have two steps, and the five largest ships have four steps. Units are not destroyed until they lose their last step, but both their combat strength and (for carriers) their ability to base aircraft decline as they take damage.

Victory is determined by Prestige. Players get a point for controlling South Georgia Island, East Falkland and each of the six sea zones surrounding the Falklands at the end of each turn. They also get points for sinking the opponent’s major naval vessels.

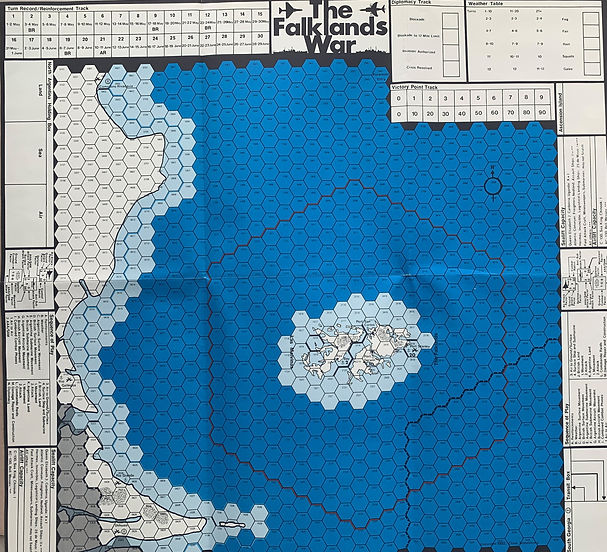

The Falklands War, published in the same year by Conflict Games, is a more conventional and complex wargame. It has a map covered with a standard hexagonal grid, 36 spaces by 30. It covers May 1 to June 29 in 30 turns, two days per turn.

Land units have anti-aircraft as well as ground combat and movement factors. Air and naval units have different attack factors for anti-air, surface and anti-submarine combat, as well as a defense factor and either movement (ships) or range (aircraft).

Most combat happens within a hex. Only Argentinian Exocet missiles can attack at a two-hex range. Air forces must be given specific missions: Combat Air Patrol, Interception, Escort, Airstrike, Close Air Support or Airlift. As in War in the Falklands, combat occurs in sequential rounds: Air to Air and Surface to Air; then Air to Surface; Surface to Surface and Submarine; Naval Bombardment; Ground to Ground.

Supply is important, especially in maintaining ground units on the Falkland Islands. This is especially important for the Argentinian player, who must decide whether to try and move units and supplies by sea, or relying on re-supply by air.

The game has an interesting mechanism for pacing the conflict. At the beginning of the game, Britain has only declared a blockade. The British player gets points for destroying Argentinian units within 200 km of the Falklands, but loses points for destroying units outside that zone. The British may bombard and raid but may not invade.

The British player rolls a six-sided die each turn. Each time a six is rolled, a marker advances a space on the Diplomacy track. The first advance allows a blockade all the way to the 12-mile limit along the Argentinian coast. The second advance reflects the Thatcher government’s authority to invade the islands.

However, the next advance is to a space labelled Crisis Resolved. This ends the game. At that point, players get points for enemy naval, air and land unit destroyed (varying with size and strength) and for occupying the key locations in the islands. The margin of victory may be Marginal, Substantial or Decisive depending on the spread between the winner’s and loser’s totals.

Another game took a more detailed look at the land campaign to recapture East Falkland and the capital of Stanley. Port Stanley: Battle for the Falkland simulates this month-long campaign with units representing half battalions and individual batteries and hexes 2.8 km across.

The British are free to choose where to make initial amphibious landings and have better troops, but face the harsh reality of an 8,000-km supply line and erratic weather that can shut down helicopter movement. Naval gunfire and air support also play important roles. Historically, the Argentinians surrendered fairly quickly once they realized the British were serious about retaking the islands. This game assumes a more robust defense.