Personal Touches

Games are usually mass-produced. They are designed to be popular and to make money. However, game design can flow from the designer's personal experiences of war. And surviving copies of old games often bear the mark of the people who played it - and their wartime experiences.

Owner's Marks

My favorite example of a game touched by a player's experience is my copy of Wir Fahren gegen Engeland. This game includes cards for every one of Britain's major ships, and the game does not end until they all are sunk.

The owner of this copy, probably a teenager too young to be drafted, carefully tracked actual sinkings of British ships. The card for each sunk ship is noted on the front with a cross, and on the back with the date of its sinking, the U-boat that sank it and the name of its commander. It even includes a "Merry Christmas" card, seen at right.

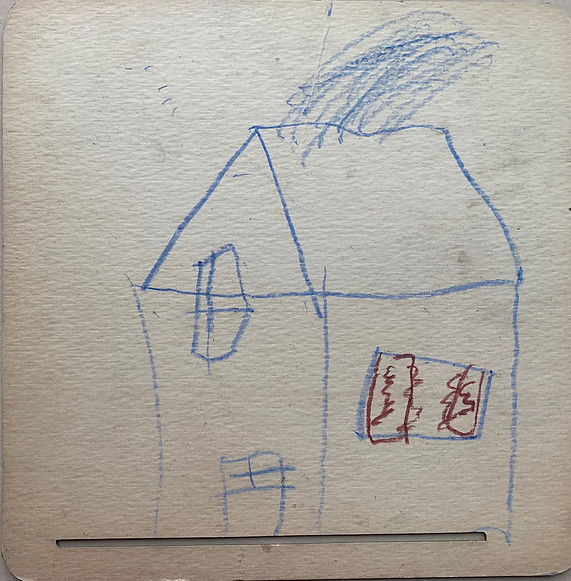

Here are a couple of other games showing signs of use. At left are scoresheets from the 1939 German game Bunker, which are used to record the locations of hidden minefields. At right is a child's drawing on the back of a player card from the 1940 American game Democracy. While not relevant to play, the copy came from the original owner's granddaughter. It also shows signs of wartime necessity as well as long use: some of the player boards have been partially cut up to provide replacement tokens.

Designer's Experiences

Some games bear very evident scars from the personal experiences of their designers. These trench scenes come from an untitled game board that bears the name of Wilhelm Teuber of Berlin. The same name appears as the co-editor of a grammar school yearbook in 1912. It is almost certain that Teuber served as a soldier on the Western Front, and that the whimsical scenes on the game board reflect the realities of his experience.

Another designer's scars are shown in the rules to Friegur, published in 1934 in Danzig - which was taken away from Germany at the end of WWI. The game is most notable for its huge bakelite playing pieces. But the game is a heartfelt remembrance of the designer's former comrades in the German army, and the rules declare his hopes for a revival of Germany's strengthen. They begin with a personal dedication:

In remembrance of the world war that broke out 20 years ago, I dedicate this game in gratitude to the German soldier, my friend Hans Kowalt, who has fallen victim, and the German youth in the sense of the word: "For the fatherland it is when we seem to play". (Editor note: from Latin pro patria est, dum ludere videmur or on behalf of your country, whilst we seem to play.)

Danzig, August 1934. E. Strey

The designer describes his desire to design a game as early as age 5. This was intensified by his wartime experiences and Germany's loss.

He wanted his game "to cling to and cultivate soldierly beings, as an opposition to pacifist thinking and an all too fast forgetfulness of the former greatness of the army and defense, and as proof that defensive thinking is firmly rooted in our people."

Even the name of the game reflects this desire, because it is an acronym for "Feldgrau rangen in Ehren, gewannen unsterblichen Ruhm", which translates as “Field grays wrestled in honor, gaining immortal fame”.

The most vivid illustration of wartime life comes from the personal experience of a French soldier captured early in WWI. His game, Les Canards du Camp, tells the story of his years in a German PoW camp. The board is laid out in a typical Game of Goose inward spiral, with images in each space as well as in the corners and center. Accompanying the game is a lengthy booklet that explains the story behind each of the images.

Some stories describe grim realities. For instance, prisoners housed in a stable were stuffed as many as eight in a horse stall, and the smart ones grabbed the oat chests, which had lids that gave a bit of privacy.

Others revel in the absurdities of camp life. Prisoners were moved around on a whim, between buildings or even between camps. The record, according to the game, was claimed by a soldier who in May 1915 was moved for the 55th time! He is shown in the game (below left) during his 23rd move, sitting on a cart with his belongings, being towed by a dog.

The Germans also appointed prisoners as internal guards to maintain discipline. But when the Germans handed out 35 armbands to designate members of the watch, “31 disappeared into our bags as souvenirs”. What’s more, the sergeant put in charge of this guard force insisted on staying in his bed. The board illustration (below right) is captioned “What we have not seen: the sergeant of the guard at his post”, and shows him being carried around the camp while still on his bed!

The designer, C. Brunlet, published the game in Switzerland after escaping from the camp in 1917. For a more complete description, see the page named "War and Remembrance".

Footnotes to History

Games, like books, tend to feature the famous. But some have mentioned people who, while they may have caught the public eye at the time, have become footnotes to history.

The 1893 British game Rubicon, for instance, features Fort Lugard, named after Frederick Lugard, a British mercenary hired by the Imperial British East Africa Company.

The company was set up in 1888 and got a royal charter giving rights to develop about 639,000 square kilometres covering what is now Uganda and Kenya. To encourage British settlement and trade, it planned to build a railway from Mombasa on the coast inland to Lake Victoria. However, conflict broke out with both other European powers and by the native residents of the region.

Lugard built the fort on a hill near Kampala and came out on top militarily, but the company quickly went bankrupt and Lugard went on to become governor of Hong Kong. The struggle, however, left the company almost bankrupt and the territory was soon taken over by the British government.

The Quartette Union War Game mentions Private Daniel Hough, the first Union soldier to die during the U.S. Civil War. He was a gunner at Fort Sumter when the Confederate bombardment signaled the beginning of the war.

The actual bombardment killed no one, but after the Union surrender on April 14, the defenders were allowed to fire off a 100-gun salute to their flag before hauling it down. Private Hough was assigned to the 47th gun of the salute. A spark denotated the cartridge early and the gun blew up, taking off Private Hough's right arm and killing him instantly.

The same game mentions Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the first Union officer killed in the war.

The 24-year-old former law clerk to Abraham Lincoln was killed by innkeeper James Jackson just after removing a Confederate flag from the latter's roof on May 24, 1861. Ellsworth is also the only non-general mentioned in the postwar game Grand National Victory.