Preventing War

Hans von Kaltenborn ran away from home at the age of 19 to fight in the Spanish-American War. Then he discovered his true vocation as a journalist, first in newspapers, then in the burgeoning field of radio.

Working for CBS through the 1930s, Kaltenborn developed a reputation for vast knowledge and insight about world affairs. During the Spanish Civil War, listeners “could hear the bullets hitting the hay above him while he spoke” while hiding in a haystack between opposing forces. He was as dextrous at covering diplomacy as warfare, and was the most respected analyst and authority on the events of the Munich conference in 1938 leading to British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain giving in to Adolf Hitler’s demands for much of Czechoslovakia in return for “peace for our time”.

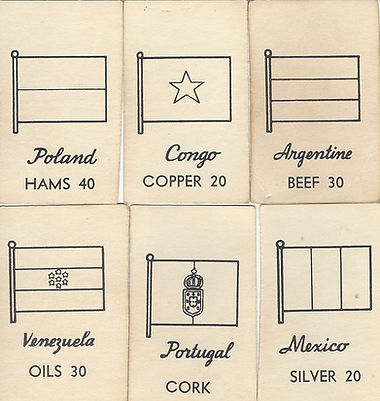

Perhaps because of his views on the outcome of the Munich Conference, he lent his name to a game published in 1939: The H.V. Kaltenborn Game of Diplomacy.

The goal of the game is to create the “greatest world empire” through threats and diplomacy rather than outright invasion.

Players represent one of the six great powers of the time, and work with one Diplomat piece, 10 consulates, 5 soldiers, 1 bomber and 1 battleship. Players use dice to move their Diplomat around the edge of the board. A player landing on a colony can place a soldier there. Landing on a colony for the second time allows replacement of the soldier by a consulate. Another player landing on a colony with a soldier eliminates the opposing army piece.

Landing on one of the two neutral countries allows players to move across the Bridge of Nations, and pick up a bomber or battleship along the way. These can be used to capture flags at a “strategic location”. The game ends when one player places his 10th consulate, and the winner is the one controlling the most strategic locations, colonies and countries.

The game is unusual on several fronts. First, it represents a global contest among the six great powers. Second, it sees conflict through the lens of colonialism and power projection rather than direct invasion of another major power. It represents a worldview that was shortly to be obliterated.

During the 1930s, the eventual combatants of WWII did not trust strictly to diplomacy and building up the quality and quantity of their armed forces. They also engaged in extensive spy operations. This field of hidden diplomacy is captured in a 1938 game, International Game of Spy.

In terms of mechanics, it is very similar to L’Attaque and other hidden set-up games of the era. However, it is designed for four players, each controlling a triangle of the square board.

In addition, the goal is not to find and capture a hidden flag piece, but rather to have a Spy penetrate to one of two known targets in each player’s territory: a Palace and a Coat of Arms. The intention in reaching either headquarters location is to steal vital secrets.

As in L’ Attaque, a player may try to move a piece into a space occupied by an opponent. Unlike the combat game, he may do so without challenging, resulting in more than one piece in a space.

The challenge phrase is “Who’s there?”, which requires both players to reveal their pieces, with the lower-valued piece being removed from the game. Each player also gets a Secret Police piece, which cannot be captured but which can only capture an opponent’s Spy. The winner is the first player to move a Spy onto one of the opponents’ target spaces.

As war broke out in Europe, the threat of espionage became a more urgent focus of public attention on both sides of the Atlantic. In Germany, this can be seen in the game Achtung! Feind Hört Mit! (Attention! The Enemy is Listening!).

As the rules put it: "In this game you have to track down a traitor who is about to escape across the border with his briefcase containing important information about our fortifications."

One player takes on the "dangerous" role of the spy, which the rules suggest should be taken on by a parent or older relative. The other players take pieces representing the army, air force, police, border guards, workers (Reichsarbeitsdienst) and Hitler Youth. The two-section board is a map of a town with streets connecting 21 circular spaces.

The spy starts in the hotel in the lower right corner of the board. He wins by reaching the Zollhaus (border post) at upper left. The other pieces start at various locations around town. Each piece moves to an adjacent space in turn, starting with the spy. Each piece must move unless completely blocked. The other players must cooperate in surrounding the spy, but the player who closes the trap wins the game.

In the United States, Columbia released a 15-part adventure serial called the “Flying G-Men” in 1939. Three government pilots, one of them disguised as “The Black Falcon”, are on the hunt for an enemy spy ring. This ring, headed by a mystery man called “The Professor”, killed one of their colleagues when who tried to stop the theft of the secret McKay aircraft.

They discover an even bigger plot to infiltrate all military factories and airports, but of course eventually get their man and rescue a lovely damsel in distress in the process.

To boost the series, Ruckelshaus Game Corp. publish a game: The Black Falcon of the Flying G-Men. The box shows the Black Falcon and fair damsel along with aerial mayhem, and adds “Dynamiting the Lid Off the Foreign Spy Menace!” It is a simple roll-and-move game. Two to four players race around a map of the United States, vying to capture the most enemy spies. These appear whenever one of the players lands on an airport and pulls a Spy Card to show where the next villain will appear on the map.

While some Americans worried about the risks of war, others simply hoped to stay out of the conflict. In 1939, Parker Brothers published The National Game of Peace for Our Nation.

In play, this works sort of like a bingo or lotto game. Each player has a rectangular card divided into eight boxes across the top. Each of these boxes has a slogan at the top and then two rows of two dots. These slogans represent American values: Liberty for All, Justice for All, Freedom of Speech, Freedom of the Press, Freedom of Worship, Industrial Harmony, National Unity and National Defense. Each pair of dots has a two-digit number above it. Along the bottom of the player card is a “reserve row” of dots numbered 1 to 9.

The game has a deck of cards made up of single-digit number cards and “three star” cards with slogans. These cards are placed face down and turned over one at a time.

Players initially put a token onto the corresponding number in the reserve row. Beginning with the second card, players may combine any two reserve tokens that match one of the two-digit numbers on the top row of their card, and put them on those top spaces. If a card is revealed and a player’s corresponding reserve space is already occupied, he does not place any token.

If one of the “three-star” cards is revealed, players may immediately place a token directly onto one of the spaces under the corresponding slogan. If this results in a single space left open, this space may then be filled if a revealed card plus a reserve token can match the space’s number.

All spaces in the top row must be filled before a player can start adding tokens to the second row. The first player to complete the card wins.

Another American game, published a year later, seemed to echo the advice of Roman general and strategist Publius Flavius Vegetius: “Igitur qui desiderat pacem, praeparet bellum.” In English, that is the well-known phrase suggesting that those who want peace should prepare for war.

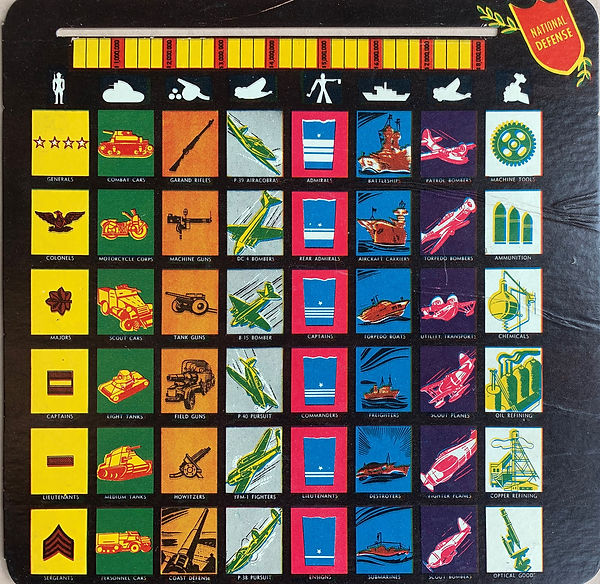

The name of the 1940 game Democracy sounds political, but it is very much about ensuring the preservation of democracy by preparing for war. Each player has a bingo-type card showing the game’s 48 available “defense units” and a metal slider to show the amount of money a player has accumulated.

The corresponding tiles are held initially on a Priorities Board. As players spin their way around the board, they try to accumulate all six pieces in one of the eight categories. Two of these represent personnel, with rank insignia for army and navy. Two of them show different types of planes. Then there is one group of armored vehicles, one group of weapons, one group of ships and one group of war industries.

Most of the images on the tiles are generic, but there is one tile specifically for the semi-automatic M1 Garand rifle, which replaced the 1903 bolt action Springfield as the standard military weapon in 1936. And among six named aircraft in the next column over are two interesting planes produced by Bell Aircraft.

Right beside the Garand is a tile for the P-39 Airacobra. This was Bell’s first successful design and it had unusual features. The engine was placed behind the pilot, leaving the nose free for a 37 mm cannon. Its main disadvantage was the lack of a supercharger, which meant its performance dropped off badly at higher altitudes. It therefore found little use in the European theatre, but was pressed into service in the Mediterranean and in the Pacific, notably during the Guadalcanal campaign. But about half of the 9,554 Airacobras produced went to the Soviet Union through the Lend-Lease program. Air combat in Russia tended to occur at lower altitudes, and five out of the top ten Soviet aces scored the majority of their kills while flying this fighter.

Further down the column is a tile for a much less successful Bell design. It is labelled the YFM-1 but was better known as the Bell Airacuda. It was Bell’s first attempt to build a military plane and it also had a very unusual design. It was supposed to be a “bomber destroyer”, a heavily-armed pursuit plane.

It had two pusher engines, and a 37 mm cannon shooting forward from each engine nacelle. It needed a crew of five: pilot, co-pilot/navigator, a radio operator who also manned the rear-firing machine guns, and a gunner in each nacelle to keep the 37 mm cannon loaded. It first flew in 1937, but proved to be too heavy and too slow for its intended role. Only 13 were ever built.

International relations got even more complicated as various powers went to war. The 1940 American game Tactics tried to capture the choices facing both belligerent and neutral nations in such uncertain times.

Tactics is intended for four players. Two of these are the North and South belligerent powers. They start the game at war with each other. The East and West powers are neutral at the start of the game, but may be pushed or choose to enter the war on one side or the other. All four powers start with equivalent forces: naval, air and merchant ships.

Cards also grant submarines at hidden locations on the board, as well as air raids. The two powers at war try to establish a blockade of their opponent’s home port while keeping their own trade routes open. The neutrals score points by trading with any other power.

The winner of the war gets a pile of gold that counts for victory points, and loses points for each piece lost. Neutral nations can accumulate gold points simply by trading with one another or with either belligerent.

The neutrals also tend to end the game with more ships since they will get into the fighting later if at all. Belligerent powers can gain points by attacking neutral shipping, but this triggers a Diplomatic Protest. The third such protest against a power drives that neutral into the war on the opposing side. Neutrals may also choose to jump into the war (on the side they believe will win), because then the gold award for winning the war gets split.

The 1936 game Liners and Transports included an unintentional portent of the maelstrom ahead. First published in 1918 as The New U.S. Merchant Marine, its peacetime map showed post-WWI changes in control such as the Japanese mandate over former German possessions such as the Caroline Islands. It also had a space marked “Terrific Storm: Total Destruction” just south of the Japanese home islands. Two of the closest cities shown are Nagasaki and Hiroshima.