The Cold War

In July, 1947, an article appeared in the magazine Foreign Affairs signed by a mysterious Mr. X. The article had its roots in a telegram in February, 1946, from the United States Treasury Department to the American embassy in Moscow. The telegram asked a simple question: Why was the Soviet Union refusing to join the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund?

The answer came from the Moscow embassy’s Deputy Chief of Mission, George F. Kennan. “I apologize in advance for this burdening of telegraphic channel,” he replied. In what became known as the Long Telegram, Kennan said that the Soviets saw themselves as being in a perpetual war with capitalism; that the Soviets would use Marxists in the capitalist world as allies; that Soviet aggression was deeply rooted in Russian nationalism and neurosis; and that the structure of the Soviet government got in the way of objective or accurate pictures of internal and external realities. He then laid out what he saw as the necessary response from the United States, one of resisting every form of Soviet expansion without resort to military force.

This prompted President Harry Truman to ask for a detailed review of policy towards the U.S.S.R. by his trusted advisor Clifford Clark. His report American Relations with the Soviet Union was given to the President alone on September 24, 1946, and Truman promptly ordered that all copies be delivered to him because "if it leaked, it would blow the roof off the White House.” It stayed top secret until 1968.

The report supported the Long Telegram, and led Kennan to prepare a private follow-up report to Secretary of Defense James Forrestal in January, 1947.

His report was never intended to be public, but Forrestal gave permission for it to be published under the pseudonym X.

“It is clear that the United States cannot expect in the foreseeable future to enjoy political intimacy with the Soviet regime. It must continue to regard the Soviet Union as a rival, not a partner, in the political arena. It must continue to expect that Soviet policies will reflect no abstract love of peace and stability, no real faith in the possibility of a permanent happy coexistence of the Socialist and capitalist worlds, but rather a cautious, persistent pressure toward the disruption and, weakening of all rival influence and rival power.”

Containment became official policy. It led to the Marshall Plan to rebuild European economies. The introduction of the German Deutschmark prompted the blockade of Berlin and its resulting airlift. In 1949, the North Atlantic Treaty was signed by France, Britain, the Benelux countries, United States, Canada, Portugal, Italy, Norway, Denmark and Iceland, prompting formation of the Warsaw Pact six years later. The Iron Curtain had come down on Europe and a global war of ideology had begun.

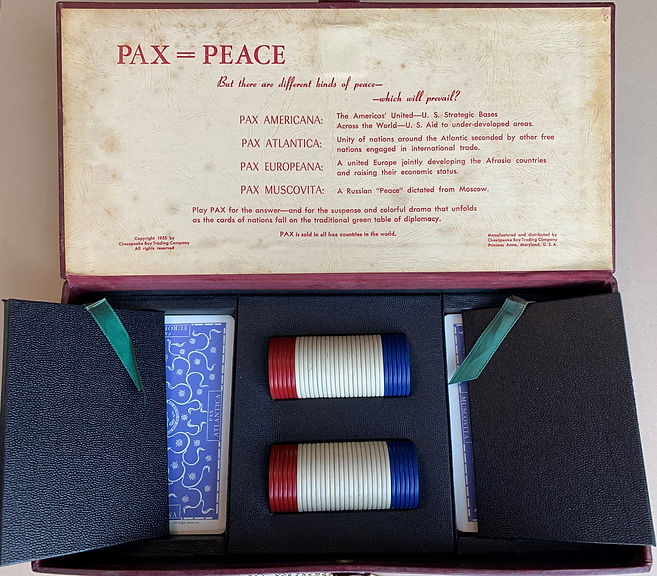

This contest of competing ideologies can be seen in the 1955 game PAX. It is a card game where players vie to establish peaceful domination of the world. The publisher, Chesapeake Bay Trading Co. of Princess Anne, Maryland, made no secret of its sympathies. The box declares: “PAX is sold in all free countries in the world.”

The game offers four possible pathways to peace. The players represent the United States, Russia, United Kingdom and either France or Germany. Their goal is to collect cards sufficient to declare one of four types of Pax:

-

Pax Americana: a united Americas with US bases around the world, focused on providing aid to underdeveloped countries;

-

Pax Atlantica: peace led by nations around the Atlantic and other trading countries;

-

Pax Europeana: a United Europe focused on boosting the economy of “Afrasia” (described as Africa, the Middle East and South Asia); or

-

Pax Muscovita: “A Russian ‘peace’ dictated from Moscow.”

The deck is made up of 48 lavishly illustrated cards. Each represents one country or group of countries. Each card has a point value (from 1 to 40), an indication of its region of the globe, and four colored bands (green, blue, purple and red). These bands show the Pax goals to which that country may contribute: Green for Americana; Blue for Atlantica; Purple for Europeana; and Red for Muscovita. If a country is not eligible for a particular Pax, that color band is replaced by a white one with a star.

After picking their starting countries at random, each player is dealt a hand of five cards and given 100 points in poker chips. They then have the option of discarding up to three cards and being dealt replacements. The rest of the deck and discards are reshuffled. The dealer then turns over the first card and commences an auction.

The winning player puts his bid into the pot and takes the card. Play continues until one player has collected the combination needed to declare a Pax. This normally consists of cards equal to 45 points in eligible countries in addition to his home country. However, it can be declared with only 35 eligible points if the player also holds cards with a majority of the possible points in one of the four regions.

The winner takes the value of the chips in the pot, and these points are recorded. Each other player subtracts the difference between his starting 100 and what he has left. These points accumulate over multiple rounds until one player reaches an agreed total. A new round begins with players again having 100 chips each.

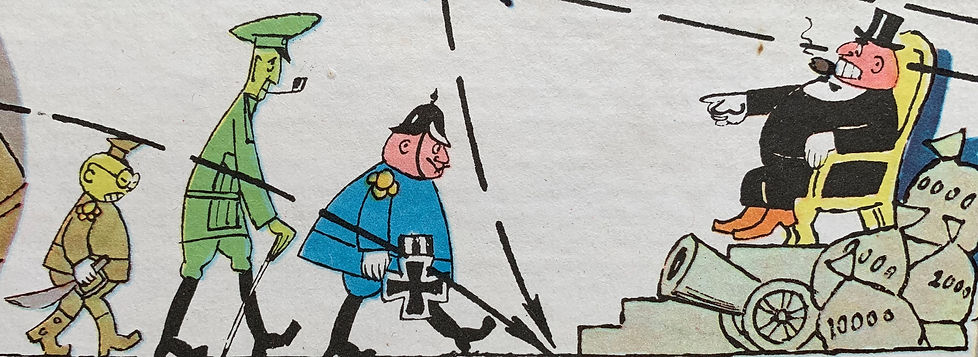

A much starker view of the East-West ideological conflict can be seen in the Soviet-era game Voennaya Taina (The Military Secret). It was aimed at children aged 7 – 9, and the rules use a chummy and paternalistic tone to deliver a pointed message. The game is based on a folk tale about a young boy who gives all to save the Motherland from the evil capitalists.

Son of a peasant farmer, he is brought into the war against the “bourgeoisie” powers, which are represented by caricatures of Germany, Japan and the United States (represented below by General Douglas Macarthur with pipe and cane).

These military enemies, however, are shown as being in cahoots, and mere errand boys for a fat banker who sits on piles of money.

The boy becomes trusted with an important military secret, and is then captured by the enemy forces. Even though tortured in a dungeon, he refuses to give up the secret, and eventually the banker orders him killed.

Inspired by his noble sacrifice, Russian forces go on to victory in the global war against capitalism. Many Russian children lost parents or close relatives during the Great Global War against Germany and eventually Japan. Soviet publisher Malish, appropriately approved by Communist Party officials, used a basic game with vivid graphics to inspire a similar willingness in the next generation to sacrifice for the greater good.

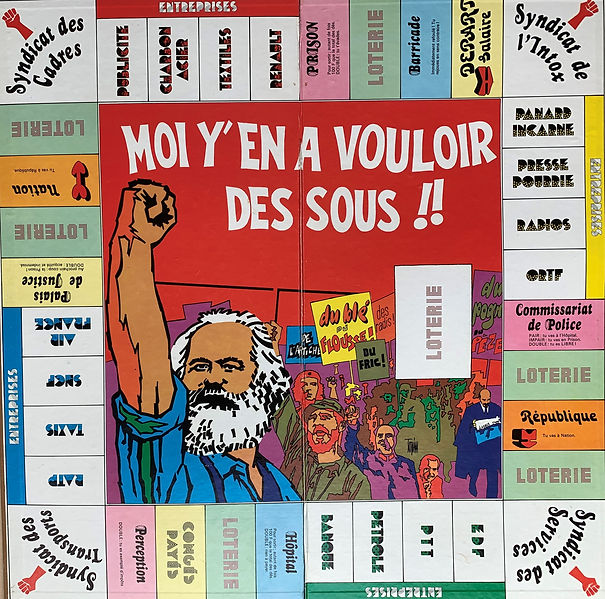

A more light-hearted and cynical view of the ideological conflict emerged from the Paris riots of May, 1968. Spurred by an electoral alliance between the French Communist and Socialist parties, students across the country mounted occupations against capitalism, consumerism and American imperialism. When police moved in to expel the occupiers, France’s trade unions called for sympathy strikes. At one point, more than 11 million workers or 22 per cent of the country’s workers were off the job. The French economy effectively shut down, and at one point, President Charles de Gaulle even fled the country. By the end of the month, however, the government, business and trade unions agreed to a big wage increase. De Gaulle then called a snap election and his party came back stronger than ever.

These events prompted a 1973 movie by director Jean Yanne. Moi y’en a vouloir des sous (Me, I just want money) was a satirical jab at all the players. It features a young accountant who gets fired from his company. He goes to work for his aunt, a big union leader. He then persuades the union to invest in a bicycle business that becomes wildly successful – and leads the accountant CEO to go on strike against the union in order to be allowed to quit.

The movie was accompanied by a game of the same name. The illustrations on the box and board reflect this cynicism. Well-known revolutionaries portrayed include Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara – but Lenin is reading a copy of the Wall Street Journal.

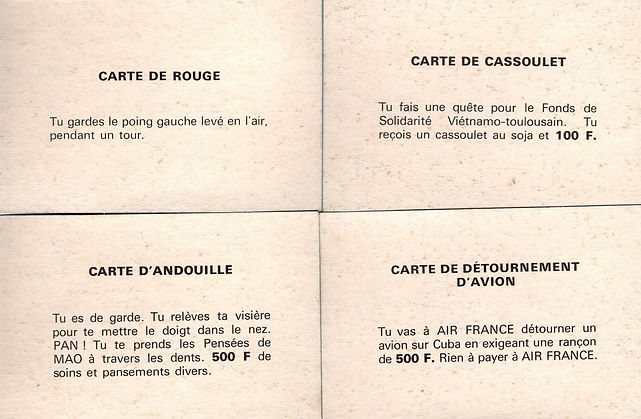

The game is loosely based on Monopoly. There is a track around the edge and players can invest in businesses they land on. However, they also vie for control of unions and can play strike cards on opposing businesses. The deck of Loterie (chance) cards reflects the tone of the movie. Some examples:

-

Red card: You must keep your left fist in the air until your next turn.

-

Cassoulet card: You raise money for the Vietnam-Toulouse Solidarity Fund. Receive 100 francs and a soya cassoulet (a stew made with meat and white beans).

-

Idiot card: You are standing guard, and you lift your visor to put your finger in your nose. BAM! You take a copy of the Thoughts of Mao through your teeth. Pay 500 francs for first aid and dressings.

-

Airplane hijacking card: You go to the Air France space and hijack a plane to Cuba. Collect a ransom of 500 francs and pay nothing to the airline.

From serious to cynical, the Cold War would provide all sorts of gaming opportunities for publishers and gamers alike. And while conflicts all over the globe would prompt related games, overshadowing all of the skirmishing was the one big question: Are you going to drop the bomb or not?