The Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War was triggered by an unexplained event and greedy newspaper owners. In 1895, Cuban revolutionary José Marti launched an insurgency campaign against Spain. That country saw Cuba not as a colony but an integral part of the Spanish state. It sent General Valeriano Weyler to put down the rebellion. He promptly began rounding up the entire population of suspect districts and interning people in “reconcentration camps” near military bases. This earned him international outrage, especially from U.S. media moguls Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst.

U.S. President McKinley wanted a peaceful resolution, and Spain backed off. It recalled General Weyler and appointed a new more conciliatory Governor General. When Spanish loyalists in Cuba threatened massive demonstrations against the new governor, the United States sent the armored cruiser Maine to keep an eye on things.

As shown in the 1898 card game The White Squadron, the American navy had by then become substantial. The deck’s 56 cards each show a U.S. warship, with the Maine described as: “The largest battleship yet contracted for by our navy. 12,500 tons displacement. Sister ship to the Missouri and Ohio, 388 feet long. A peculiarity is her submerged torpedoes.”

At 9:40 p.m. on Feb. 15, 1898, the Maine suddenly blew up, killing 250 of the 355 sailors on board.

The U.S. Navy investigated and ruled that the powder magazine had been ignited by an explosion under the ship’s keel. This theory pointed toward a Spanish mine as the cause. The Spanish investigation of course disagreed. The New York newspapers seized on the Navy finding, declaring as fact that the Maine had been sunk deliberately and printing numerous lurid stories about alleged Spanish atrocities in Cuba. The U.S. Congress voted to back Cuban independence, declaring explicitly that the United States had no intention of annexing it. The United States sent an ultimatum to Spain demanding that it set Cuba free. Spain said no, and by April 21, the war was on.

Much of the action took place at sea, both in the Pacific and in the waters around Cuba. It was a conflict that pitted a relatively modern and growing American fleet against the remnants of the once-mighty Spanish armada. And it went very badly very quickly for the Spanish.

The Game of Naval War, published by McLoughlin Bros., offers an unusually graphic image of combat, especially notable because the box features American sailors being wounded and dying in the foreground while the sinking ships in the background can only be presumed to be Spanish. On the other hand, the game's spinner features a sinking Spanish ship.

The game also has a very unusual board. The map is focused on Cuba and surrounding islands. But to the upper right, a map of the Philippines appears in what should be the direction of the Bahamas.

Each player gets five ships, with the red player starting in the Tortugas and the blue from Cadiz. Each turn, a player moves one ship by the exact number on the spinner, and captures an opposing ship by landing directly on it. All players can use the gold tracks, while the red and blue tracks are limited to their respective players.

The box cover of War at Sea, subtitled "Don't give up the ship", has equally vivid but less gory graphics on the cover. The large box has a detailed image of an American warship, likely intended to be the Maine.

However, while the ship shown has the Maine's offset turrets, it shows three funnels rather than the Maine's two (as does the card from The White Squadron at top).

The playing surface is a checkerboard of light and dark blue squares, bordered by North, Central and South America. There are 24 metal miniatures: 6 battleships and 6 torpedo boats per player. The southern end of the board is a flap that opens to show the storage area.

To start, players alternate in placing a single ship at a time anywhere on the map. In turn, each player moves a single ship. Battleships can move 1 in any direction; torpedo boats 1 orthogonally only. Either can jump over any adjacent ship (friendly or enemy) to an empty square. Enemy ships jumped are eliminated. Multiple jumps are possible. A player wins by eliminating the enemy fleet.

Unusually, the ships are larger than the squares on the board, but the rules say that they occupy the one containing the ship's bow.

The first American hero of the war was Commodore George Dewey. On May 1, his Asiatic Squadron smashed a Spanish squadron in Manila Bay, with nine wounded men as the only American casualties.

Dewey then brought Filipino rebel Emilio Aguinaldo from exile in Hong Kong. By June 9, his forces had gained control of nine of the Philippine provinces and was besieging Manila.

On June 12, he declared Philippine independence. The United States brought in 11,000 regular troops, and on Aug. 14, the Spanish forces in the Philippines surrendered.

Dewey was later promoted by Congress to the newly created rank of Admiral of the Navy, and briefly tried a run for the U.S. presidency in 1904.

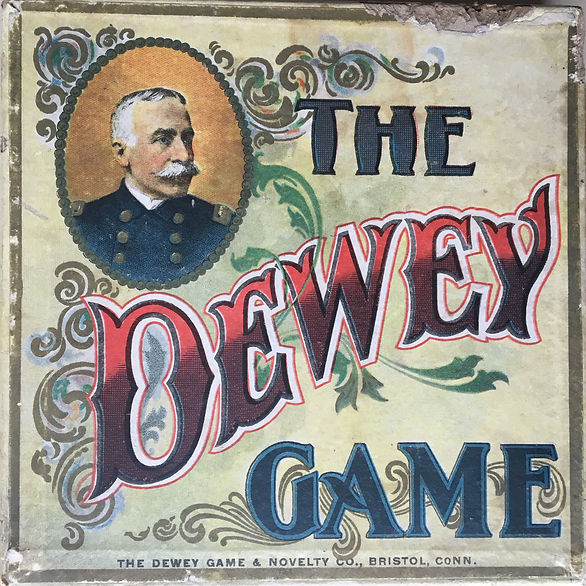

In Bristol, Connecticut, a quick-witted entrepreneur formed The Dewey Game Co. Ltd., and published The Dewey Game before 1898 came to an end.

This is a word game similar to Anagrams, but with the specific objective of forming the last names of 14 admirals who served in the U.S. Navy during or prior to the Spanish-American War.

The names run in value from Admiral Albert S. Barker (10 points) to Admiral Dewey (100 points). The game contains 77 plain square letter tiles, one for each of the letters in the names on the list of admirals. Other admirals celebrated in the game include:

-

Rear Admiral William Thomas Sampson commanded the Flying Squadron that destroyed the Spanish fleet under Admiral Pascual Cervera at the battle of Santiago de Cuba on July 3, 1898. He then sent the message: “The Fleet under my command offers the nation as a Fourth of July present, the whole of Cervera’s Fleet.”

-

Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley was actually in command at sea and won the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, because Admiral Sampson was on shore at the time. He was deeply offended by Sampson's claim of credit for the victory, and the two feuded for years thereafter.

-

Rear Admiral Frederick Valette McNair was commandant of the United States Naval Academy from 1898 – 1900. (His son Frederick Jr. was awarded the Medal of Honor for valor during the battle of Vera Cruz in 1914.)

-

Rear Admiral John Adams Howell commanded a division of the North Atlantic Squadron during the Spanish-American War. He is better known for his inventions, including the first American self-steering torpedo while still a lieutenant commander in 1870.

-

Rear Admiral Albert Kautz was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Squadron in March 1899.

-

Rear Admiral George C. Remey (mis-spelled on the card), was Commandant of the Portsmouth Navy Yard when the war broke out. He then moved to the naval base at Key West, where he was in charge of supplying and repairing naval forces in the Caribbean and making sure that ground forces in Cuba got their supplies.

-

Rear Admiral John C. Watson served as Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet starting in June 1899.

Players initially draw a hand of 10 tiles, and attempt to form, in whole or in part, names from the list. On each turn, a player draws a tile from the face-down stack, and if possible adds it to one of his names in progress.

Instead of drawing from the stack, a player may steal a face-up tile from another player. The stolen tile must be required for one of his own started names, and his own partial name must be closer to completion than his opponent's.

Letters may not be stolen from completed names. A player who a name is granted an additional tile draw.

When the draw pile runs out, players may continue to steal from one another if they can. The game ends when no further plays are possible. The winner is the player who completes the highest point-value worth of names.

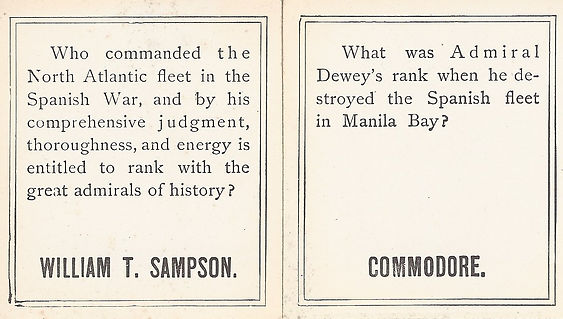

Dewey and Sampson are both mentioned in the The Card Game of United States History. An image of an American naval victory over Spanish ships adorns the front cover.

Inside this game, however, it is Admiral Sampson who gets star billing. The Dewey card simply asks what rank he held when he destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. The Sampson card, on the other hand, asks: “Who commanded the North Atlantic fleet in the Spanish War, and by his comprehensive judgment, thoroughness and energy is entitled to rank with the great admirals of history?”

One suspects that Admiral Schley probably did not purchase a copy of the game!

The Spanish-American War also prompted other lavishly illustrated board games. Parker Brothers alone published at least three games just about the war’s sea battles: Dewey’s Victory, The Battle of Manila and Siege of Havana.

The pre-war game mentioned above, The White Squadron, includes images and descriptions of many of the individual ships that took part in the naval actions on both the Pacific and Caribbean fronts.

Ships of the Asiatic Squadron under Admiral Dewey include his flagship protected cruiser Olympia, the cruisers Baltimore, Raleigh and Boston (which still had masts able to handle 10,400 square feet of canvas sails to help economize on coal use), the gunboat Concord and the monitor Monterey.

The key players in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba also are in the deck. These include Admiral Sampson’s flagship New York and Admiral Schley’s flagship Brooklyn. These were modern and powerful cruisers, but the biggest guns were on the battleships Iowa, Massachusetts, Indiana and Texas. Also represented are the light cruiser New Orleans and torpedo boat Porter.

Two other cards have interesting individual stories. The Oregon was the only American battleship based on the Pacific coast, at San Francisco.

When war broke out, she was ordered to sail for the Atlantic to reinforce the fleet there. She completed the 14,500 nautical mile journey around Cape Horn to Key West in 66 days.

There is only one Spanish ship included in the deck. This is the cruiser Reina Mercedes, which the card credits as leading Admiral Cervera’s disastrous sortie from the harbor of Santiago de Cuba. However, Reina Mercedes had been in bad shape at the outbreak of the war and was then damaged in harbor on June 6. With seven of her 10 boilers out of action, she could not have kept up with the rest of the squadron. As a result, most of her guns were removed to be used on land.

Reina Mercedes did sail a day later, on July 4, in a night-time attempt to scuttle the ship and block the entrance to the harbor. She was spotted quickly and sunk out of the main channel. The reason she is included in the deck is that she later was raised by the U.S. Navy, rebuilt at the Norfolk Navy Yard and commissioned as an unarmed American vessel.

American troops landed in Cuba on June 22. The decisive land battle took place on July 1, two days before the American navy destroyed the Spanish Caribbean squadron in the battle of Santiago de Cuba.

A total of 15,000 American troops, including regular infantry and cavalry as well as four regiments of “colored” troops and assorted volunteer units such as Theodore Roosevelt’s “Rough Rider” regiment, made a frontal assault on 1,270 Spanish troops dug in on San Juan Hill.

The Americans took the hill, but at the cost of 200 dead and 1,200 wounded. The battle made quite a few reputations.

First Lieutenant John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, for instance, led the 10th Cavalry forces in the battle. He was cited for gallantry and went on to general’s rank in WWI.

But no one garnered more fame than Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders.

Parker Brothers published The Rough Riders in 1900. The box cover features a very recognizable image of Theodore Roosevelt leading a line-abreast charge. The game is a simple roll-and-move game. Up to 10 players can start from the Camp at the bottom of the board and race up separate winding tracks toward victory at the top of the hill.

The game's spinner is interesting not for its graphics but for its form. There is an inner ring of results from 1-6, with an outer ring of 36 small spaces, showing a 1-6 result for each of the inner segments. The result may be the first spinner designed to mirror the throw of two normal dice.

An actual photograph of U.S. land forces in Cuba is included in the 1903 Cincinnati Game Co. card game Our National Life. This deck is made up of cards commemorating American achievements in war, territorial expansion, commerce and industry, finance, invention, education and religion. The Cuba land card is matched with one showing the wreckage of the Maine in Havana harbor.

The deck also includes two territorial expansion cards related to the war. One notes the addition of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam to the territorial possessions of the United States as a result of the 1898 treaty ending the war, as well as the annexation of the Hawaiian Republic in the same year. The matching card has a photo of “a Philippine school” under U.S. management, with the racist and imperialist comment that in assuming control of the Philippines, the United States also “takes up the white man’s burden” in order to “develop among them and their people a modern civilization”.

As the U.S. public revelled in their country's new status as an up-and-coming empire, an even larger country was about to come to grief at the hands of a small island nation.