The American Civil War

Colonel Elmer Ellsworth was not really expecting resistance as he approached the Marshall House. For weeks, the inn in Alexandria, Virginia had been flying a huge Confederate flag, right across the Potomac River from the White House. On May 23, 1861, the state of Virginia voted in favor of secession. The next day, as Ellsworth led Union troops across the Potomac River to occupy the town of Alexandria, he decided that the flag had to go.

Ellsworth was only 24. He had joined Abraham Lincoln’s law office as a clerk in 1860 and followed the President to Washington after his election. With war looming, he headed to New York, where he raised the 11th New York Volunteer Regiment, mostly from among the city’s firefighters, and brought the unit back to Washington.

The regiment ran into no resistance as it moved into Alexandria, and Ellsworth took only four troopers with him into the Marshall House. He went to the roof and took down the flag without any trouble. But the innkeeper, James Jackson, was both a zealous defender of slavery and a violent man. As Ellsworth descended the stairs, Jackson leapt out of a side passage and fired his shotgun at point-blank range. He killed Ellsworth instantly and in turn was cut down by one of Ellsworth’s men, Private Francis Brownell, who first shot Jackson and then stabbed him repeatedly with his bayonet.

Since a reporter was on the scene, word of Ellsworth’s death quickly made it back to the White House. President Lincoln reportedly exclaimed: “My boy! My boy! Was it necessary this sacrifice should be made?” Ellsworth became the first Union officer killed in the Civil War, during which many more American lives on both sides were sacrificed.

As the Duke of Wellington observed after Waterloo, “Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.” Most wartime games emphasize optimism going into war or glory while the fighting goes on. But some have captured brilliantly the costs of war, even to the victors.

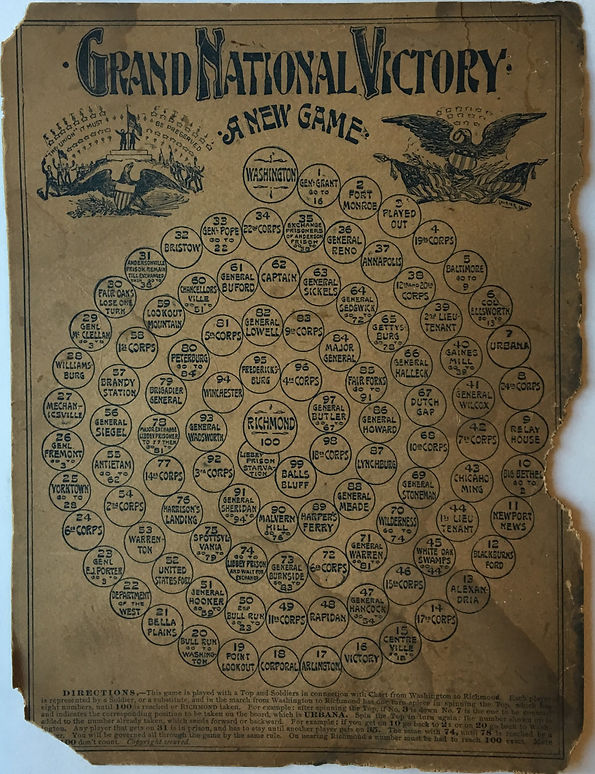

Ellsworth is the only colonel to be named in the post-Civil War game Grand National Victory. Its 100-space track runs from Washington to Richmond, and tells the tale of the long and bitter struggle from the perspective of the unnamed Union veteran who designed the game.

Colonel Ellsworth appears on space number 6, and moves the player landing on him ahead to space 13, which is labelled Alexandria. Each space is marked either with a battle or key location, the name of a general or other officer, or the name of a unit that took part. As described on the back of the board, “The players represent the rank and file of the Union Army, and meet with similar reverses in the struggle to capture Richmond, the Rebel capital; it presents to the mind of every Veteran as to the author of this game, a retrospective panorama of his struggles to save the Union…”

The names appear in roughly the order in which they played key roles in the war. The bonus and penalty spaces in turn reflect battles and officers that either helped or set back the Union’s drive to victory. Battles lost send the players backward: Bull Run (space 20) sends the player back to start; Second Bull Run (50) returns the player to 23; and Chancellorsville (60) goes back to 51.

The self-inflicted wounds of poor leadership also create setbacks: General F.J. Porter (23) goes back to 9; Generals John C. Frémont (26) and George B. McClellan (29) both send the player back to 3. General Porter was court-martialled in 1863 for disobedience and insubordination while commanding V Corps at Second Bull Run.

General Frémont was court-martialled long before the war, for insubordination and mutiny for taking control of California in 1846. But he was given command of the Department of the West by President Lincoln at the outset of the Civil War and recorded the only 1861 Union victory in the West at Springfield. He also is notable for first spotting the “iron will” of Ulysses S. Grant and promoting him to command. The meticulous but notoriously cautious McClellan raised the Army of the Potomac and served as general-in-chief of the Union Army in 1861-62, but was relieved of command after the battle of Antietam.

Similarly, bonus spaces reflect key victories and successful leaders. For instance, Gettysburg (65) leads forward to 78; Wilderness (70) to 74; and Spotsylvania (75) to 79. Generals Grant (1), Gettysburg hero Winfield Scott Hancock (47), John Sedgewick (64), Gouverneur Kemble Warren, “the Hero of Little Round Top” (71), Ambrose Burnside (73) and Philip Sheridan (91) all move the player forward, as does Colonel Ellsworth (6).

Oddly, General “Fighting Joe” Hooker (59) provides a bonus despite being best known for his stunning defeat by General Robert E. Lee at Chancellorsville (60) in 1863. For that matter, Sedgewick was best known for his last words – “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance” – just before being killed by a Confederate sharpshooter at Spotsylvania Court House in 1864.

Most poignant are the spaces that represent soldiers being captured and sent to either the Andersonville or Libby prisoner-of-war camps. A player landing on either of these is trapped, and can only move again when another player reaches the corresponding prisoner exchange space. As the ultimate heartbreak, a player who lands on space 99 dies of starvation in Libby, on the very cusp of victory.

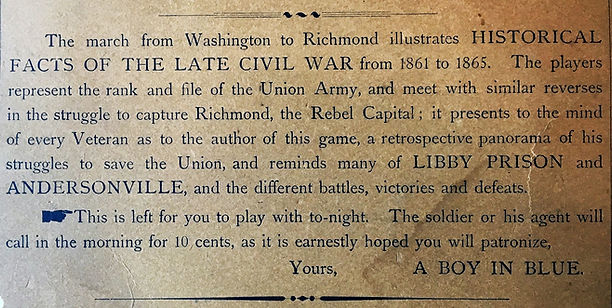

What makes this game unique is that it speaks to the post-war costs of victory as well. The pitch on the back shows that it was sold door-to-door by unemployed Union veterans.

“This is left for you to play tonight. The soldier or his agent will call in the morning for 10 cents, as it is earnestly hoped that you will patronize.”

The letter is signed “A Boy in Blue”, and to drive home the patriotic appeal, the remainder of the back side of the board is devoted to the lyrics of “We Saved the Union for You”. It closes with a challenge:

“In a short time, those who risked their lives that this Union should remain unsevered, will have passed away, and you, who were children during those gloomy days, will soon be expected to assume control of this great Nation. Will you prove worthy of the trust? And when we, who sacrificed so much have gone, will you remember we saved this great Union for you?"

The Civil War also lent itself to simple card games similar to Dr. Busby, Authors or Happy Families. Wartime versions included home-made decks that had nothing more than names of generals and battles. As time went on, more sophisticated versions were issued by major publishers.

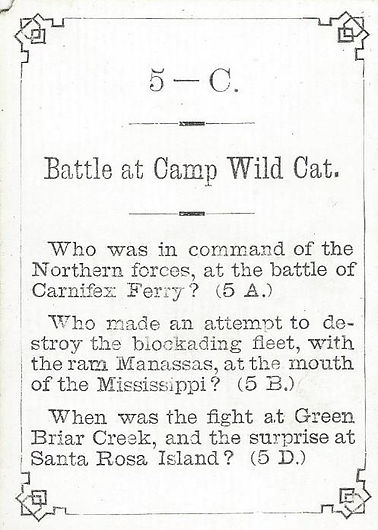

The Quartette Union War Game, for example, was published by E.G. Selchow & Co. in 1874. Each card features a title and three questions as well as the number of its set and a letter from A to D. The correct answers to the questions are the titles of the other cards in the set.

While the rules permitted players to ask for cards simply by number and letter, the deck could be used as an educational or trivia game. In this case, players asking for cards had to request them by calling out the correct answer to questions on their cards.

For instance, cards 5-A, 5-B and 5-D include one each of the following questions. What brisk battle took place on the road to the Cumberland Gap? What battle was hugely encouraging to the Union inhabitants? At what battle was General Thomas in command? The answer, which is the title of card 5-C, is the Battle at Camp Wild Cat.

This battle took place on October 21, 1861, during an early Confederate campaign in eastern Kentucky. It was a skirmish by the standard of later battles. The two sides combined totalled only about 12,000 men, and only 16 (5 Union and 11 Confederate) were killed. However, it was one of the first Union victories of the war.

Card 5-A gives credit for the victory to Brigadier General George H. Thomas, but the Union troops were actually commanded by Brigadier General Albin F. Scheopf, who was sent by Thomas to reinforce the initial small garrison of Camp Wild Cat.

Another card in the deck, 1-B, commemorates the first Union casualty of the war. Private Daniel Hough died as a result of the Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter in April, 1861.

No soldiers on either side were killed during the battle itself. However, after the American surrender on April 14, the defenders were allowed to fire off a 100-gun salute to their flag before hauling it down.

Private Hough was assigned to the 47th gun of the salute. Shortly after loading the gun, a spark set off the cartridge prematurely. The gun blew up, taking off Private Hough’s right arm and killing him almost instantly.

Colonel Ellsworth, mentioned above in Grand National Victory, also rates a card in this deck. The game includes costs other than human lives as well, with Card 9-D recording that by the end of the first year of the war, the national debt had reached the then stupendous sum of $491,448,384.

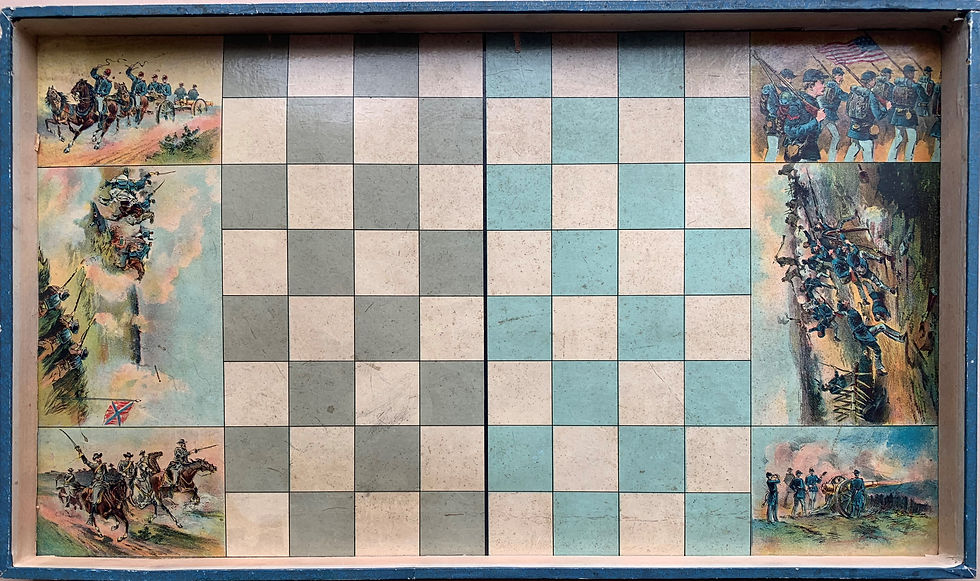

Standard games like checkers and chess took on wartime livery. This Civil War set has dramatic illustrations of soldiers in action at both ends, from artillery bombardment to hand-to-hand combat.

The game came with colored wooden disks. These had an image on one side and a plain back. The images show different types of military men, from bugler to general, which could be placed and played as a form of chess. And the plain backs enabled players to use it for checkers as well.

While of the Civil War's bloodshed occurred on land, naval strategy played a key role in the Union victory. Its superior navy allowed it both to land troops along the coast, and to throttle the economy of the Confederacy by shutting off its exports of cotton as well as imports of war materiel.

Running the Blockade was published near the end of the war by Charles Magnus, a printing company that mainly supplied patriotic stationery and penny song sheets. The elaborate lithograph features several major naval events of the Civil War.

This includes an illustration of the Trent Affair in 1861. A Union ship stopped and boarded the Trent, a British steamer, and seized two Confederate diplomats on their way to Europe. The English were incensed, and there were calls in London for Britain to enter the war in alliance with the South. However, abolitionist sentiments and cooler heads prevailed after the Union returned the two diplomats. The board also illustrates the Confederate commerce raider Nashville, and the sinking of the Alabama in September 1864.

It was designed as a competitive maze. Players started at one of the entrances on the lower edge, and had to keep pencil or pointer touching the paper as they moved forward. As soon as they ran into a dead end or one of the illustrated blockading ships or scenes, their turn was over and the next player began. The first to reach the central illustration of the harbor at Wilmington, South Carolina, was the winner.

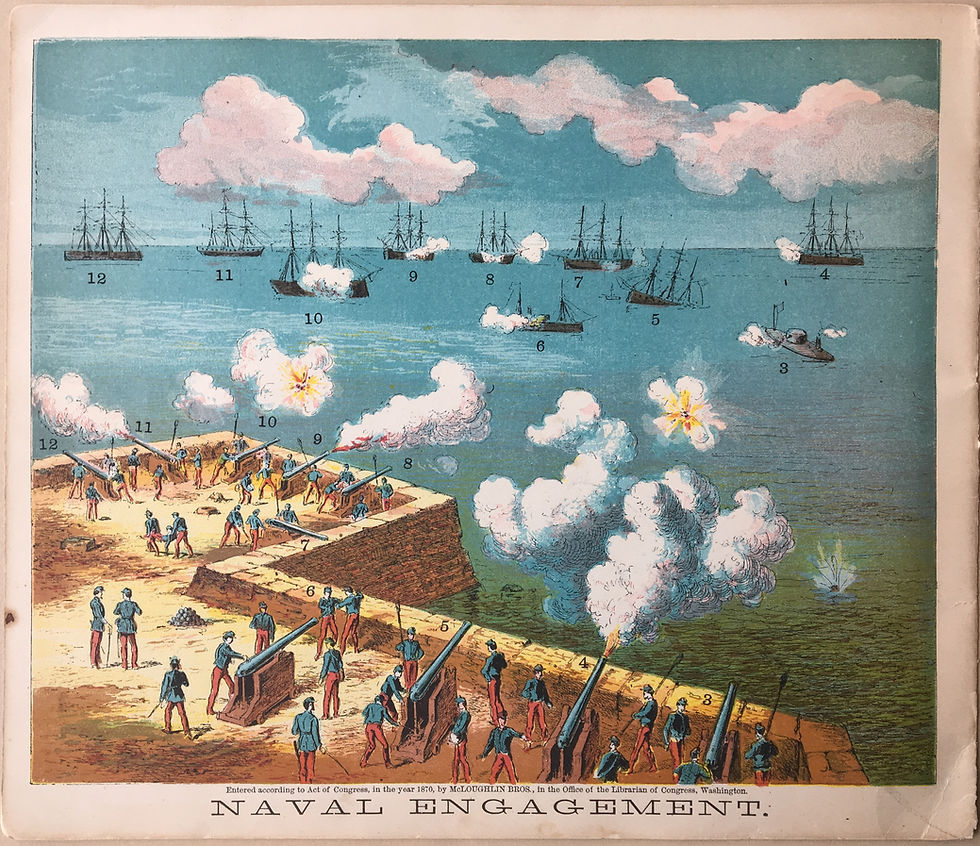

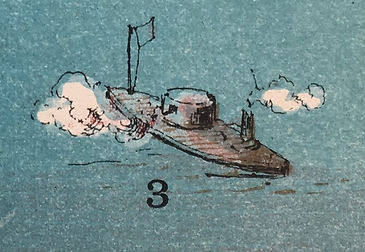

An 1870 McLoughlin Brothers title, Naval Engagement, is notable for being the first game to include a picture of an ironclad warship, in this case a Union Monitor-class ship. This is a die-rolling game. The attacking player has 10 ships and the defender 10 shore guns, each numbered from 3 to 12. Players roll two six-sided dice, and mark off the opposing ship or gun with that number. Duplicate rolls are wasted. The first player to knock out all the opposition units wins. The game was re-released in 1898 as Game of Bombardment.

Even as the United States began to heal the wounds of civil war, another major conflict was brewing between two traditional European rivals.