Despots and Decolonialization

Africa

In southern Africa, war was sparked in 1972 by an employee who hated his boss. Rex Nhongo worked at a tobacco farm in the northeast corner of what had become the pariah nation of Rhodesia. The farm was owned by Marc de Borchgrave, then just 37 years old. De Borchgrave was generally disliked by his employees, and Nhongo for some reason bore a special grudge.

On Dec. 21, 1972, Nhongo led a squad of 10 members of the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) from their base within the Chiweshe Tribal Trust Territory north toward the village of Centenary. They were armed primarily with AK-47s and grenades, with one light machine gun.

The group also came armed with a list of white farmers in the area. They crossed off the names of those known to be sympathetic toward their black workers. Nhongo made sure they settled on de Borchgrave’s farm of Altena as the target for the night.

At 3:00 a.m., the guerillas cut the phone lines and buried a land mine in the farm’s driveway. They then snuck up on the farmhouse and on signal sprayed it with assault rifle fire and threw grenades in the windows. While the structure was riddled, the only injury was to de Borchgrave’s eight-year-old daughter Jane. The farmer managed to evade the guerillas and fled on foot with his family to seek help. The guerillas in turn retreated after expending their ammunition on the house. Nhongo himself was actually stopped and questioned by police in the aftermath, but having dumped his weapons, was allowed to go on his way.

The Altena Raid, as it became known, is considered the opening battle in what became known as the Bush War in Rhodesia. There had been bombings and assaults from time to time since Rhodesia’s unilateral declaration of independence in 1965. The Altena Raid marked a shift to continuous military conflict between the government and the two main opposition groups: the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU); and Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU).

ZAPU, led by Joshua Nkomo, eventually developed strong ties with the Soviet Union and focused on building up conventional forces from its base in Zambia. ZANU, led by Robert Mugabe and based in Mozambique, turned instead to the People’s Republic of China and pursued a broader campaign of internal subversion. ZANU’s military arm, the ZANLA, conducted the Altena Raid.

The Rhodesian government, led by Ian Smith, essentially had no friends. By 1975, even the apartheid government of South Africa was predicting its demise. So while Communist rivals Russia and China were heavily involved, it never turned into one of the many East versus West proxy conflicts of the Cold War.

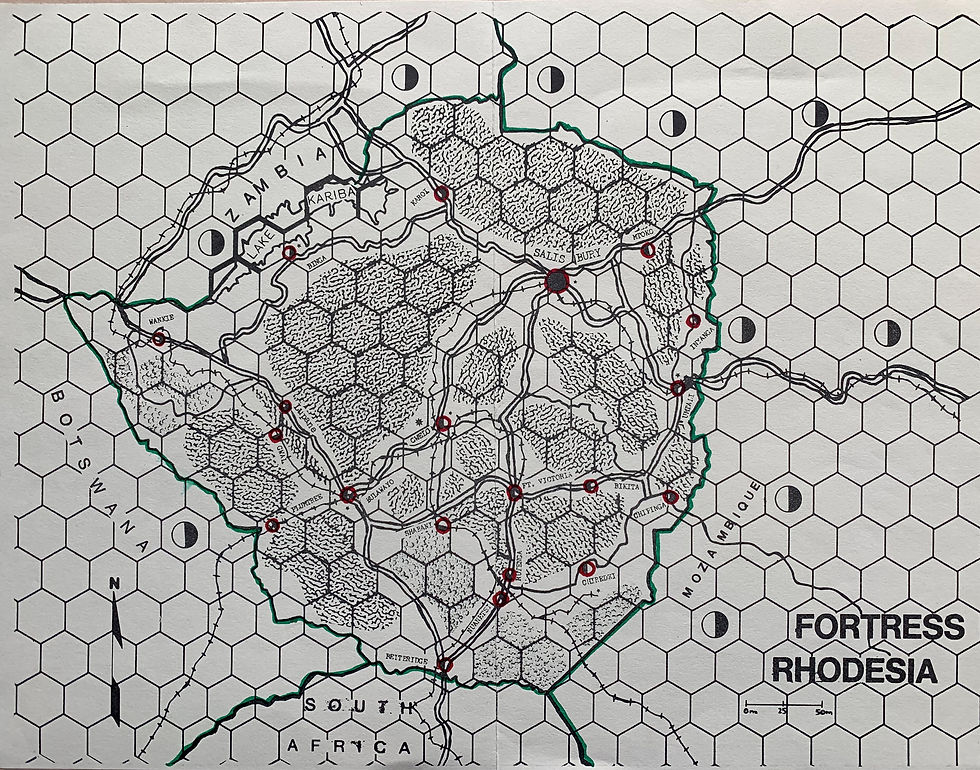

It did, however, prompt a contemporary wargame, Fortress Rhodesia. This pits the government’s army, air force and police against ZANU and ZAPU, and lasts 24 turns. As a self-published game by designer Michael J. Raymond, its production quality is basic, with a black-on-brown paper map and cut-out counters in blue and red intended to be glued to cardboard by the buyer.

The game does an excellent job of capturing all the elements of the two-year campaign. The Rhodesians start with excellent troops backed by airpower, but cannot replace losses and are reinforced only with lower-quality reserve units. The guerrillas are weaker individually, but multiply as the game goes on. They also get a dummy unit for each guerrilla unit. All their units move face down, and are exposed only if attacked. The battle is highly fluid, since units exert no control on adjacent spaces and can move into and retreat into an enemy-occupied space.

The guerrilla player gets victory points primarily for capturing or destroying Rhodesian infrastructure, including cities, air bases and the vital chromium production plant in the middle of the country. The Rhodesian player may get points for capturing or destroying guerrilla supply spaces in neighboring countries, but pays a victory point penalty for crossing borders. A space is captured by moving through it; destroying it requires both eliminating any defenders and successfully remaining there through an enemy turn. A captured space may be recaptured, and guerrillas may rebuild destroyed supply bases.

Whites in Rhodesia were outnumbered by 22 to 1. As in the actual Bush War, their regime cannot win this game in the end. The government player’s victory is measured by how long it holds key objectives, and how much damage it can do to insurgent forces in the meantime.

The South African government faced similar pressures, but was in a much stronger economic and political position. Apartheid (white rule) eventually was defeated, but without full-scale military conflict.

That possibility was very real, however, and prompted development of the 1977 game South Africa: Vestige of Colonialism. This two-player game was published in Strategy & Tactics # 62. It simulates a possible military revolt of forces representing the country’s Black majority against the White-run government.

This game is neither one of political influence nor of guerrilla insurgency. It assumes that the conflict has deteriorated into a set-piece military campaign.

Units represent company to battalion level units fighting to control a map of the entire country. The map scale is 60 kilometers per hex, and each turn represents one week of real time.

Victory points are awarded for destroying the other side’s units and for controlling key locations within the country. If any player achieves a victory point ratio of 3:1 over the other, the game ends immediately with an automatic victory. There is no time limit on the game, but the rules anticipate that the South African government will eventually be toppled. In other words, the Government’s success is measured by how long it lasts rather than whether it can win in the end.

As it happened, the government gave in to increasing international pressure and negotiated a peaceful transition toward Black majority rule. In 1990, Prime Minister F.W. de Klerk lifted the ban on the African National Congress and released political prisoners including Nelson Mandela. In 1993, he agreed to hold South Africa’s first all-race democratic election, and on May 9, 1994, Nelson Mandela was elected as the nation’s first post-apartheid president.

Elsewhere in Southern Africa, even a peaceful transition from colony to independent country was often marred by conflict over control of the new nation. One of the longest-running post-independence wars was in the former Portuguese colony of Angola.

No sooner had independence been achieved in 1975 than the two major liberation movements began fighting. The communist People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) had its base in the Ambundu people and the main cities. The anti-communist National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) had its base in the Ovimbundu people of central Angola, who represented about a third of the country’s population. Two other groups played significant roles pre- and post-liberation. The National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) fought with UNITA for independence but faded in activity during the civil war. The Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) aimed for the breakaway of its small but oil-rich region.

The initial conflict was captured by the wargame Angola designed by James Rosinus and published in 1979 by Gameshop and Nova Game Designs.

This was a small wargame with a single mapsheet and only 140 counters. In addition to normal ground movement, there are helicopter and fighter counters to provide tactical air support.

One unique feature involves supply. Units need only trace a line to a source in friendly territory to move. Attacking, however, requires consuming a supply unit that is within range. Since the same supply unit can support all attacks within its range that turn, coordination of offensives is critical. The game sold few copies, but greater things were to come, on the ground and on the tabletop.

The conflict quickly became a proxy battleground for all of the main Cold War rivals.

The MPLA had been supported by the Soviet Union since the 1950s. It received major troop contributions from Cuba, and both training and financial support from President Tito’s communist regime in Yugoslavia.

UNITA went through an astonishing range of supporters. China was a big backer before independence but the United States became its biggest supporter after the beginning of the civil war and increased support steadily. By the latter years of the war, the still-apartheid regime in South Africa took over as its biggest backer.

Superpower intervention reached a peak in the late 1980s.

In 1986, the Soviet Union gave $1 billion to the MPLA government. That same year, US President Ronald Reagan invited UNITA leader Savimbi to a meeting at the White House, portraying him as a star in the fight against Communism, and announced the provision of anti-aircraft Stinger missiles as part of a $25 million aid package. In 1987, Cuba added 3,000 troops to the 12,000 it already had in the country.

This set the stage for largest military battle in Africa since El Alamein in WWII. From Jan. 13 to Mar. 23, 1988, UNITA and South African forces attacked the MPLA’s base at Cuito Cuanavale in the southeast corner of the country. Cuban troops were alleged to have used nerve gas against UNITA troops, a claim backed up by a Belgian observer.

The news coverage of this intense period of the civil war prompted another game called Angola. This one was developed by Adam Starkweather and published by another small company, Ragnar Brothers in the United Kingdom. Unlike its 1979 predecessor, this Angola became a cult classic, and was republished in much glossier form by Multi-Man Publishing in 2012.

The game owes its popularity to some highly innovative rules. In particular, players do not move all of their units, one side at a time. Instead, they commit to moving a limited number of their units in secret and in a set order. This forces players to guess where their opponents will focus their efforts and make their own choices accordingly. The victory point conditions are finely balanced, and the fact that it is a four-player rather than two-player game makes for memorable game sessions.

This image of the mapboard from the MMP edition is a huge contrast to that of the 1979 game. The later game uses area movement rather than a hex grid. And although both games address the impact of road networks and terrain, the evolution of graphics and color over the intervening decades is very clear.

Whatever the truth, the results of the massive battle were inconclusive, with both sides claiming victory, and all sides agreeing to hold truce talks.

Northern Africa also saw its share of conflict during the Cold War. While it did trigger some intervention from former colonial powers, much of the fighting was between new claimants for national control, often with help from neighbors.

Target: Libya was published in 1986, in Strategy & Tactics # 109. It hypothesized that the United States might strike back at Libyan dictator Muammar Qaddafi for his suspected support of numerous terrorist attacks. On April 12 of that year, the United States did just that with Operation Eldorado Canyon.

From Britain came 18 F-111 bombers and 4 EF-111 electronic countermeasures aircraft. From the carriers USS Coral Sea and USS America came 24 more aircraft. These used anti-radar HARM missiles for the first time in combat to suppress Libyan air defenses. They then dropped 60 tons of bombs in 12 minutes, hitting the airfield at Tripoli, a naval academy, and army barracks in Benina and Jamahiriya. Only one plane was lost.

Target: Libya assumes an invasion rather than an air raid. Its 200 units include air squadrons, naval units and infantry brigades. The U.S. player’s goal is to seize Libyan leaders and strategic locations while keeping losses low.

Long before Colonel Qaddafi triggered the ire of the United States, he was meddling in the one-time French territory that became Chad. That country lies along Libya’s southern border, and Qadaffi was never shy about wanting to expand his territory and influence.

Chad hardly seems worth fighting over. It has been one of the poorest countries in the world since independence in 1960. Its northern border region had potential for uranium mining but the country had no developed resources through the 1980s. Much of the country is desert, where temperatures can hit 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade. The middle of the country turns into desert when regular droughts hit. The 1983-85 drought killed some 200,000 people, 4% of the population.

But the population is riven by both ethnic and religious divisions. Even French control was loose, and independence brought a constant military tension. The game Chad: The Toyota Wars appeared in Strategy and Tactics magazine #144 as a particularly vicious decade came to an end. The game gets its name from the Toyota pick-up trucks mounting assorted guns and missiles used by rebel leader Hissene Habres in his 1987 campaign.

The game subtitle covers the years 1979 to 1988. However, the rules note that Qadaffi was supporting rebel groups in the 1960s and include a scenario for yet another rebellion that doesn’t start until 1990, the year before the game’s publication.

The game reflects the chaotic and ever-changing nature of the conflict. It is set up as a two-player contest between Habre, commander of the Armed Forces of the North (FAN) and Goukouni Oueddei, head of the People’s Armed Forces (FAP).

However, the rules include 15 factions, each with its own acronym. Many of these factions appear as independent guerrilla groups. These can be persuaded to join either side, and may switch sides abruptly.

For that matter, if the rebel side occupies the capital of N’Djamena, it becomes the government player!

This in turn affects the country's relationships with the foreign countries that may supply money and troops. The game includes foreign troop counters from France, Libya, Nigeria, Kenya, Congo, Senegal and Zaire. There also are air units and money from the United States.

Winning is not about decisive military battles. The rules reflect the reality that with armed forces totalling 40,000 men operating over 500,000 square miles, decisive combat is almost impossible. Winning essentially requires maintaining just enough control over enough regions to keep the economy afloat.

As the designer concludes in his notes: “Corruption, mismanagement, and incompetence are endemic in many Third World societies; but the combination has been particularly devastating for Chad. The protracted civil war decimated the population, destroyed the nation’s structures, collapsed the education system, and paralyzed trade and agriculture. Successfully playing a simulation of all this is a real challenge. (But then, it wouldn’t be fun if it weren’t!)”