War in the Pacific

President Franklin D. Roosevelt almost lost his son on a remote island in the Pacific in 1942. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the President ordered the formation of an “unconventional warfare” unit that would be like the British Commandos. He assigned the task to Lt. Col. Evans Carlson, who at one point served as head of his guard detachment. More importantly, Carson had served three tours in China, where he got to know Mao Zedong and became inspired by the Communist approach to guerrilla warfare. Maj. James Roosevelt came on board as Carlson’s deputy.

Carlson disdained the social separation between officers and enlisted men. He redesigned the squad structure, and had the unit adopt the motto of “Gung Ho”, a mispronunciation of two Chinese Mandarin terms meaning roughly “everyone work together”.

All this made him a black sheep within the Marine flock, but presidential influence got him the time, space and equipment to forge the new unit, which he called the Marine Raiders.

Their first operation was an assault on Makin Island, a Japanese seaplane base in the Gilbert Islands. It almost was a disaster. The 221-man assault force was carried in two large submarines, the Nautilus and Argonaut. The submarines arrived off Makin late in the evening of Aug. 16, 1942. Unexpectedly rough seas carried away the first two landing boats and swamped the engines on many others. Carlson decided to consolidate the landing at a single beach instead of two.

The Raiders finally made it ashore at 5:00 a.m. on Aug. 17. One of them promptly fired a shot accidentally, alerting the Japanese garrison. The advancing Raiders ran into the Japanese response force around 6:00 a.m. and a vicious firefight ensued. At 7:00, Carlson called in supporting artillery fire from the submarines, which then also destroyed a transport and a patrol boat in the lagoon. At that point, the Japanese forces conducted two consecutive banzai charges at the Raiders, with the result that most of the Japanese were cut down at short range.

The Japanese tried to land reinforcements by flying boat at 1:30 p.m. but these were destroyed as they tried to land in the lagoon. And that was that, or so Carlson thought. However, when the Raiders tried to withdraw from the beach that evening, none of their motors would work and heavy surf made paddling out to sea extremely difficult. By midnight, 11 of the 18 boats had made it back to the submarines, but Carlson, Roosevelt and 70 other men remained stuck on the island.

In despair, and in the hope of saving the life of the President’s son, Carlson wrote an offer to surrender and sent it off with a Japanese prisoner. That didn’t work either. A Raider unaware of the surrender attempt shot the Japanese soldier as he headed back to the island’s base.

A few more boats, including one with Roosevelt, made it out by morning, and then Carlson decided to have the remaining men sweep through the Japanese base and rendezvous with the Nautilus in the lagoon. They set fire to the island’s gasoline stores, and successfully returned to the sub.

Nine Raiders were inadvertently left behind on the island. They were captured, moved to the island of Kwajalein, and then executed on the orders of the commanding Japanese admiral. Had Carlson succeeded in surrendering, he and Roosevelt could well have suffered the same fate. Instead, they returned to Pearl Harbor as heroes. The military impact of their raid may have been small, but in the early days of the Pacific War, this first attempt to fight back was a huge morale booster.

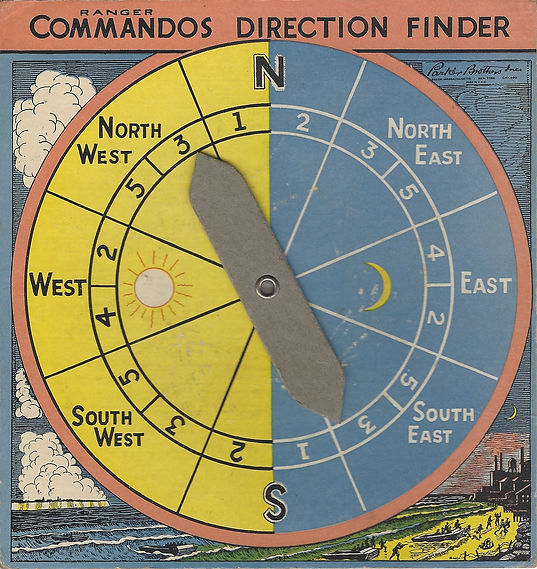

Although not named as such, the Marine Raiders were shortly celebrated by a new game from Parker Brothers, Ranger Commandos. The game depicts a raid on a Japanese-held island, and the mechanics capture rather well the chaos of the Makin experience through the use of an innovative set of playing pieces and an unusual spinner.

The spinner shows results for three different situations. On the way in, the wooden boats move in the direction shown by the pointer on the night side, generally toward the island but sometimes sideways. On land, a player’s soldier piece must move by exactly the number of spaces shown on the inner ring. And on the return voyage, boats use the outer-ring results on the day side.

When a boat lands, the wooden soldier peg jumps out and moves along island paths. The player must move the exact number shown on the spinner.

The objective is to reach the arrows providing entrance to various buildings such as the oil storage, airfield or headquarters. Improbably, this minor Pacific Island also contains an airplane factory, a tank factory and a munitions plant!

The objectives contain one to six face-down yellow tokens worth between zero and 100 points. The buildings with the most tokens are furthest away. A player may not take more than one token from any objective.

Along the way are posted Japanese sentries. As soon as any raider unit is forced to land on one of the sentries, the alarm is sounded. At that point, players have just three spins to make it back to their boats. Players who miss the deadline are captured and out of the game, which introduces a real push-your-luck element.

Once back aboard, the boats make the difficult return voyage, and there is a big bonus for the team that returns to base first. This means that a player who fails even to reach the island before the alarm sounds still has a chance to win the game!

Japan, for its part, continued its tradition of sugoroku-type games to pump up wartime spirits. An example from 1941 is the Heitai San sugoroku, which appeared in a magazine for Grade 2 students.

This is a straightforward and rousing recruitment pitch, showing young Japanese men in a wide variety of roles and locations. These include a sentry on guard in northern snows, a beach assault by Special Naval Landing Force troops, and images of artillery, tanks, cavalry, transportation, medical and engineering troops in action.

Unusually (given the eternal conflict between the Japanese army and navy commands), the game also offers images of warships and of naval bombers. No American opponents are shown because it was published before the attack on Pearl Harbor. The young recruits are shown in the central victory square shouting “Banzai!”

Another pre-Pearl Harbor Japanese game was this version of a slide-em puzzle showing Japan working with Germany and Italy to deal with Britain, France and the Soviet Union.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, when it did come, was a surprise to American armed forces and game publishers alike. For instance, Van Wagenen & Co. of Syracuse, N.Y. had just published Game of Defense.

Its board is a map of the North and South Atlantic Oceans. The abutting land areas are blank. The oceans are divided up into a red and white checkerboard pattern. There are four “objectives” on each side of the ocean.

Each player gets 15 ships. Five are battleships, five are cruisers and five are submarines. The battleships move only on red squares in any direction, up to four squares in a single move. The cruisers move only on white, with a range of three. Battleships and cruisers capture other ships by jumping over them.

Submarines move only one space, but onto any square. Submarines capture ships by moving onto their squares.

The plastic pieces, which came in two different versions, are painted with red and white stripes on the bottoms to identify the battleships and cruisers.

There is a special rule allowing up to five ships touching one another to move as a fleet. Finally, each player secretly writes down 10 minefield spaces; an opponent landing on a minefield must draw a random results card that may sink the ship, force it to lose a turn or reverse course.

The initial game was not about the Battle of the Atlantic: the two players represent the United States and “Europe”. Players secretly choose one of the five objectives. The player must get one or two ships to touch the opposite shore at that location to win. The Americans must get one to Scapa Flow, Lisbon or Dakar, or two to Brest or Gibraltar. The Europeans need one to New Orleans or Panama and two to Halifax, New York or Charleston.

When war with Japan broke out, the company was quick to publish a new edition: Game of Defense: Pacific. Both games used the same box and label. The only difference was the addition of a small sticker saying either Atlantic or Pacific slapped onto the front of the box.

The rules stayed the same. Only the map and the objective cards changed. The Japanese player’s four possible objectives are 3 ships to Los Angeles; 2 ships to Santiago, Chile or “Kadiak”, Alaska; or a single ship to the (Panama) Canal Zone. The American player must get 3 ships to Yokohama, 2 ships to Paramushiro (an island to the north of Japan that was turned into a major air and naval base) or “Sidney”, Australia, or a single ship to Saigon.

Milton Bradley rushed to market with Bataan, whose lavishly illustrated box commemorated the ultimately unsuccessful American defense of the Bataan peninsula in the Philippines. Inside the box, however, was simply another version of the large Game of Siege (Grosse Belagerungsspiel).

Kroll Publishing dealt with the abrupt opening of the Pacific campaign by slapping a new title, Two Ocean Navy, on a standard paper and pencil Battleships game.

The company went further by issuing three versions differing only in the unit names and symbols shown on the bottom of the sheets. There was a land game, Tanks in Action, and an air game, Air Defense.

The Two Ocean Navy game title actually referred to one of the most critical actions taken by the U.S. Congress in preparing for a possible war in the Pacific. A few days after the fall of France in June, 1940, the House of Representatives passed the Two-Ocean Navy Act. Spearheaded by Rep. Carl Vinson, the chair of the House Naval Affairs Committee, the act passed 316-0 after only one hour of debate. It authorized $8.55 billion for a massive expansion of the U.S. Navy. Furthermore, it focused the expansion on naval air power. As Vinson put it, “the carrier, with destroyers, cruisers and submarines grouped around it, is the spearhead of all modern naval task forces.”

In other words, almost a year and a half before Japan attacked, Congress authorized construction of 18 new aircraft carriers and 15,000 naval airplanes, while adding only seven battleships. The bill also provided for 33 cruisers, 115 destroyers and 43 submarines.

When the Japanese attack of Dec. 7, 1941 knocked out Battleship Row in Pearl Harbor, it merely reinforced the decisive shift to air power in American naval strategy.

The Battleships format was popular because it could be printed on paper, at low cost and with no need for war-essential materials. Companies even seized on the game as a form of advertising. This version of Salvo (below left) came from the Signal Oil Company, pitching both its patriotism and its brand of (rationed) gasoline. The cover includes an image described as an “actual scene taken aboard submarine showing under-sea-men playing favorite game, Salvo”.

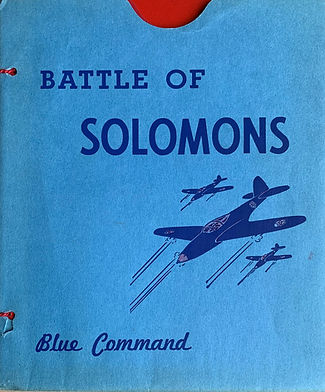

A much more elaborate version, Blast 'Em, was published later in the war by Electric Game Co. This comes in a pebbled binder that contains Red and Blue pockets for three distinct battles: The Battle of Britain in Europe and Midway and the Solomons in the Pacific. The binder also contains a pocket for "reload" sheets and a rules page.

The playing boards all have irregularly shaped land areas within the standard 10 x 10 grid. There is a different mix of land and sea areas for each battle (as shown above right). These restrict where players can place their forces. The Battleship and Submarine spaces must be at sea, the Land Battery and Tank Force must be wholly on land, and the Air Squadron can be anywhere.

In Australia, a publisher took a more dexterous approach to naval combat. Navy Bobs offered two different ways for players to try to sink the opposing navy.

A channel runs up the middle of the box bottom, with ships printed on either side. Indents in the bottom of the channel are potential hits on the corresponding ships. In one version, players place the wooden ball at the near end of the channel, and poke it with a wooden cue stick through an opening in the end. Alternatively, they can set up a cardboard "torpedo tube" angled down into the channel,

Players then roll the ball down toward the targets. In either version, players take turns shooting. A player whose ball lands in a target hole pegs the corresponding location on the opposing ships. Another hit in the same location counts for nothing. The first player to completely sink the opponent's ships wins the game.

Innovation in warfare led to innovation in game mechanics. The war in the Pacific was the first naval war completely dominated by carriers. The Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor smashed much of the U.S. battleship force, but missed the carriers. That said, Japanese carriers outnumbered American ones until after the Battle of Midway.

The 1944 game Flagship recognized the growing importance of air power. It is a straightforward extension of checkers.

The board is one space larger in both length and width (9 by 9), and pieces are placed and move only on the dark spaces. Each player’s home rows therefore have five available spaces in the back rank and four in the second rank.

Each player gets seven destroyers and one flagship, plus one aircraft carrier.

The flagship moves like a checkers king. It moves one space in any diagonal direction. It takes an adjacent enemy piece by jumping over it to an empty space.

The destroyers act like normal checkers, gaining flagship powers if they reach the final rank.

The game has small wooden rings that get put onto the destroyer pawns to show their new status. The aircraft carrier is the only piece with new powers. It is allowed to move as many spaces in a line as it wishes, and can jump over (and take) any enemy piece that has an empty space immediately behind it, even if that enemy is several spaces away.

While recognizing the extraordinary new powers that aircraft carriers brought to naval warfare, the game still assumes that the commanding admiral would be found on a battleship. The aircraft carrier pictured is a reasonable attempt at drawing a Yorktown-class ship rather than the Essex-class ships that were being launched by date of publication.

During the initial phases of the Pacific campaign, pilots were at a premium. The Navy therefore expanded its practice of allowing some enlisted men, usually non-commissioned officers, to be trained as pilots. These pilots were designated Naval Aviation Pilots or NAPs.

VF-2, the fighter squadron on the aircraft carrier Lexington, was known as the Flying Chiefs because it was made up almost entirely of NAPs. The unit’s logo features the eagle and hashmarks from the NAP insignia.

This fighter squadron is one of 17 naval air units whose logos are featured in the All-Fair card game Squadron Insignia. During the early war, air units on a carrier were assigned a number matching the carrier's, with a prefix designating their role. VF-2 was the naval (V) fighter (F) squadron assigned to Lexington (CV-2). Similarly, the prefixes VB, VT and VS signified bombing, torpedo and scouting squadrons respectively. A second digit was added if a carrier had more than one squadron of a given type. The game’s cards simplify the unit identities by referring only to their role and number.

All-Fair seems to have taken some liberties with the artwork on the box and on the backs of the cards. Both feature what looks very much like a Martin PBM Mariner flying boat. This was a state of the art long-range patrol bomber that entered service in 1940. There is just one problem: the Mariner has only two engines and the artwork shows four.

The artwork on the card includes the logos from most of the early-war carrier squadrons.

Squadron logos shown on the cards include VF-3’s Felix the Cat holding a bomb (from Saratoga), the star and eagle of VF-5 (the Striking Eagles of Yorktown), the boar’s head and lightning bolt of the original Red Rippers (VF-41, of the Ranger), and VF-71 and VF-72 of the Wasp, including the latter’s “Blue Burglar” wasp caricature.

Similarly, the deck includes torpedo bomber and dive bomber squadrons from the Lexington, Saratoga and Yorktown, as well as scouting squadrons from Lexington, Yorktown, Enterprise, and Ranger.

Many of these squadrons were disestablished as the Lexington, Yorktown and Wasp were sunk during 1942, and their colorful logos have faded into memory.

A few, however, remain in service. The Ranger’s scouting squadron VS-41 was turned into a fighter squadron (VF-42) on the same carrier in 1943. This is now the oldest continuously active squadron in the American navy, with its top hat logo now registered to VFA-14. The unit is based at Naval Air Station Lemoore in California. The logo and nickname of the Red Rippers (VF-41) now belong to VFA-11, while Felix the Cat and his bomb live on with VFA-31. Both are based at the Naval Air Station Oceana in Virginia.

The workhorse of carrier-based dive bombers was the Douglas SBD Dauntless. Its initials came from “Scout Bomber Douglas”, but it also acquired the nickname “Slow But Deadly”.

The scouting designation came from the fact that it was designed to have a long range, which proved to be especially important to its bombing role in carrier warfare. It also had a unique set of perforated flaps on its wings, which helped keep it stable while diving.

Dauntless bombers accounted for many of the American kills of Japanese aircraft carriers, including the Shoho in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Akagi, Kaga, Hiryu and Soryu at the Battle of Midway and the Ryujo during the Guadalcanal campaign.

A diving Dauntless just releasing its bomb got star billing on the cover of the Junior Bombsight Game published by Otis-Lawson Co. in 1942. The inside of the box is raised, with point-valued cardboard targets mounted on hinges.

The game also has a three-tube bombsight made of heavy cardboard. Two of the tubes provide a binocular sight, with cross-hatch plates for aiming. The third parallel tube is used for the bombs. These are white marbles that the players drop one at a time through the tube. Players use the game’s bombsight to aim their shots, and the winner is the one to rack up the highest total score.

The game was published shortly after Pearl Harbor, and may be the first to feature targets that are specifically Japanese. The game board includes both naval and land targets. The swinging targets with the highest values are a warship and a submarine both shown as sinking. However, Japan’s red ball on white background appears on a flag over an exploding dockside factory on the board, as well as on a two-engine bomber and an aircraft hangar that appear on two other swinging targets.

Dart guns, spring-loaded cannon and elastics propelled a wide variety of target-shooting games to popularity during the Pacific campaign. Shown here are Air Defense, Air Raid Defense, Mechanical Airplane Target Game (with spinners) and Coast Defense.

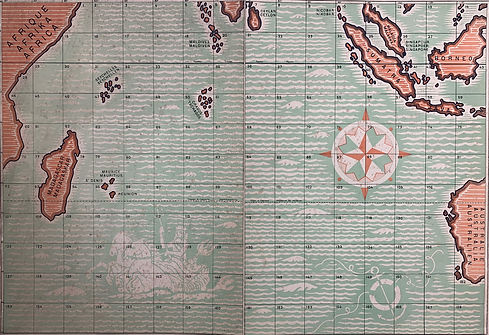

The most innovative and interesting strategy game dealing with the Asia-Pacific theatre had nothing to do with the American island-hopping slog to victory. Rather, it is based on the early-war incursion of the Japanese fleet into the Indian Ocean. This was a major highway for transporting resources from Britain’s Asian possessions. Shipments of rubber were especially important for war purposes.

Defending the Indian Ocean was the job of the British navy. Most of the action in this region involved submarines and commerce raiders. The only major fleet encounter involved a massive raid by the Imperial Japanese Navy in March-April, 1942.

This was made possible by the fall of Singapore in February, 1942 and the subsequent capture of the Andaman Islands. Allied strategists expected that an invasion of Ceylon was coming next. The Japanese navy planned to do exactly that, but the Japanese army refused to cooperate. Instead, the navy sent Admiral Chuichi Nagumo on an aggressive mission to find and destroy the Ceylon-based British fleet.

Nagumo had a large force including five aircraft carriers, four battleships, seven cruisers, 19 destroyers and five submarines. The British Eastern Fleet under Vice Admiral James Somerville had been reinforced by major units after Pearl Harbor. All told, it was roughly equal in numbers, with only three carriers but five battleships. The British, anticipating the attack, moved out of port and waited south of Ceylon.

At dawn on April 5, Japanese planes bombed the port of Columbo, and a Japanese airstrike sank the heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire that afternoon.

Over the next four days, the two fleets searched fruitlessly for one another, even though at one point they were only 120 miles apart. The Japanese did spot and sink several other warships, including the aircraft carrier Hermes, two destroyers, an armed merchant cruiser and a corvette, as well as 23 merchant ships. On April 8, they launched a major raid on the port of Trincomalee.

By then, Somerville had realized that he faced a much larger force than the two aircraft carriers that had been expected. He therefore opted to retreat. The Eastern Fleet rebased to Kenya in eastern Africa.

However, Japanese attention moved elsewhere, and after the battles of Coral Sea and Midway in May and June respectively, the naval threat to the Indian Ocean pretty much evaporated.

A major fleet action in the Indian Ocean was the subject of the Belgian wargame Batailles sur Mer. Although published just after the war, the artwork on the box may have been commissioned during Axis occupation. The game as published put the title on a large red sticker that was affixed over the middle of the box. A peeling sticker shows that the covered art features the twin tail of a plane that looks suspiciously like that of a Messerschmitt 110. Also, the forces in the game are abstract, not naming any national combatants.

However, the game mimics the 1942 Japanese raid on Ceylon. Each player has an aircraft carrier, a battleship, two cruisers, two torpedo boats and two submarines. Allowing for the torpedo boats as representing the lighter forces, this does reflect the historical mix if not the numbers of that battle.

The game mechanics also do a remarkable job of simulating the difficulty of finding and attacking an opposing fleet within a large body of water. It may be the first wargame to use a “double-blind” system. Each player has a separate playing board and they face away from one another.

Players take turns moving secretly, and only give away their potential location by announcing an attack against a specific square. The number of shots per ship and their range and direction varies by the type of ship. However, any announced attack gives some indication of location.

The game includes both red metal shell bursts to mark hits and dummy wooden ship counters to plot possible positions. The game pre-dates the double-blind rules for Avalon Hill’s Midway by two decades.

Moving back to the simplicity of dexterity games, Trap a Sap gives a sense of the violence involved in the U.S. island-hopping slog toward the Japanese main islands. Players try to juggle three beans through a small hole into a cardboard enclosure. The background art shows infantry and a tank at the bottom.

Part of a battleship is seen in the middle, with two burning Japanese planes overhead. This clearly references the kamikaze threat facing American ships as they moved ever closer to Japan.

The game with the best illustration of the Allies’ big-picture strategy in the Pacific is the similarly titled Trap the Jap in Tokyo.

It too is contained within a box only 4.5 inches (11.4 cm) square. Both the game’s lid and the bottom of the box shows a map covering the entire war zone from eastern India to Alaska and Australia.

The board (below right) has a total of nine indentations: four white circles, four blue circles and one red, and the glass-covered box has small marbles in matching colors. The goal is to fill all of the indentations at once with marbles of matching color.

The pattern re-creates the gradual strategic encirclement of Japan. The four white holes represent the American island-hopping strategy: the Marshall Islands, the Solomon Islands (Guadalcanal), Timor in the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines. The blue circles represent broader strategic goals, from recapturing Attu in the Aleutian Islands and Singapore in the south, to retaking the island of Guam and going after Japanese forces in China. The specific target there is the city of Foochow (Fuzhou), on the coast of Fujian province, which was scouted early in the war as a potential staging ground for an Allied invasion of Japan. The final red hole, of course, is Tokyo.

In the end, of course, Tokyo was firebombed but Japan was never invaded. Instead, the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, together with the Russian declaration of war and invasion of Manchuria, prompted Japan to sue for peace in August 1945. World War II was over.